India made a strong post-pandemic recovery, leapfrogging the UK to become the fifth largest economy in the world.1 This essay delves into the role that Self-Help Groups (SHGs) based in India played in achieving this remarkable turn-around. The unprecedented challenges posed by the pandemic required a major reassessment of existing management principles and strategies.

Peter Drucker, one of the greatest management pioneers of all time, who lived through two world wars, might have been hard-pressed to make sense of the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, Drucker’s keen analytical mind would surely have been intrigued by the complex interplay between the priorities defined by public health, governance, and economic recovery in the backdrop of the pandemonium and chaos taking place in the world’s biggest democracy, India. Respectfully, even Drucker too may not have seen how key a role Indian

SHGs would play in what is being lauded today as a remarkable recovery for the nation. The following is an attempt to understand different elements of this success story.

SHGs in the Indian Context

Self-Help Groups differ from geography to geography in terms of their definition and functions. In Western countries, a self-help group is thought to be a collection of people who come together to help each other overcome mental or physical hurdles such as addiction or self-harm. Alcoholics Anonymous and Life Ring are two notable examples of Western self-help groups. However, in the Indian socio-economic context, a Self-Help Group (SHG) is a voluntary association comprising of 15–25 members, consisting mainly of, but not exclusive to, women who band together under a common umbrella with shared economic and other interests.

The primary goal of an Indian SHG is to facilitate micro-lending to achieve the long-term goal of social and economic upliftment of its members. Members of SHGs are required to make deposits into a joint savings account on a regular basis, and, in turn, they gain access to loans at favorable interest rates from the account. Once an SHG starts maintaining a track record of consistent repayments, audits, regular meetings, and a transparent electoral process, it is legally allowed to interact with the financial sector.

The specific role played by SHGs in the development of countries such as India:

- Combat Rampant Poverty: Most rural societies lack access to basic services such as credit, healthcare, and education. This hinders overall development and perpetuates the cycle of poverty in societies. SHGs aim to bridge the gap by providing microlending facilities, promoting the culture of saving, and facilitating access to other important resources. Together, SHGs empower members, liberating them from grip of poverty and enhancing their socio-economic well-being.

- Fight Systemic Gender Inequality: In Indian society, as in others globally, women have often been confined to subordinate roles like caregivers or domestic assistants. While progress has been made in reducing such discrimination, significant disparities persist in areas like employment, education, and healthcare access. Gender inequality remains pervasive in India, with women being excluded from numerous opportunities. SHGs empower their members, mostly women, through education, skill building, and self development. SHGs also provide a platform for women members to challenge age-old patriarchal societal norms and encourage them to participate in the decision-making process.

- Strengthen Social Cohesion: Self-help groups promote both economic progress and social cohesion. By uniting individuals, these groups establish a supportive network that fosters collaboration, knowledge exchange, and communal aid. They offer a platform for members to address societal matters, tackle community challenges, and undertake initiatives for the collective good. SHGs help build social capital that fosters stronger and more resilient communities.

India’s network of rural SHGs, where women from similar socio-economic backgrounds pool their savings and manage their credit interests following the principles of solidarity and mutual interest, has grown over the years. This has helped women become more enterprising, take more risks, earn financial independence, and demand greater participation in the decisions taken in their homes and villages.

The ‘Baba Jaleswar Self Help Group’ is a pertinent and powerful example of individuals coming together over shared interests. This group was formed by 10 women who had taken up pisciculture but would often face serious hardships meeting their expenses when they would net a bad catch.2 The initiative thrived, with 12 ponds and a growing membership. Members share responsibilities for feeding, selling, and maintaining the

ponds. These empowered women, belonging to various self-help groups, emerged as primary providers for their families during the pandemic. The government supported many SHGs with subsidies for their equipment and provided loan assistance at the time.3

SHGs have proven themselves to be an important asset to the Indian economy and are considered key players in expediting development in the rural sector, especially in the context of extension of modern financial services. Given the significant challenges that rural communities continue to face, the Government has duly recognized the work done by SHGs and has launched policies to aid their initiatives and bolster their growth and development.4

The Socio-economic Impact of the Pandemic

The world’s largest democracy, India was brought to a standstill in March 2020 when the Government declared a complete halt to any unnecessary social or physical contact. The socalled lockdown began. The lockdown diktat displaced millions of low-wage workers, domestic helpers, and others who relied on physical labour as a means of earning. A massive crisis unfolded that overwhelmed the Indian Government hamstrung by limited resources.

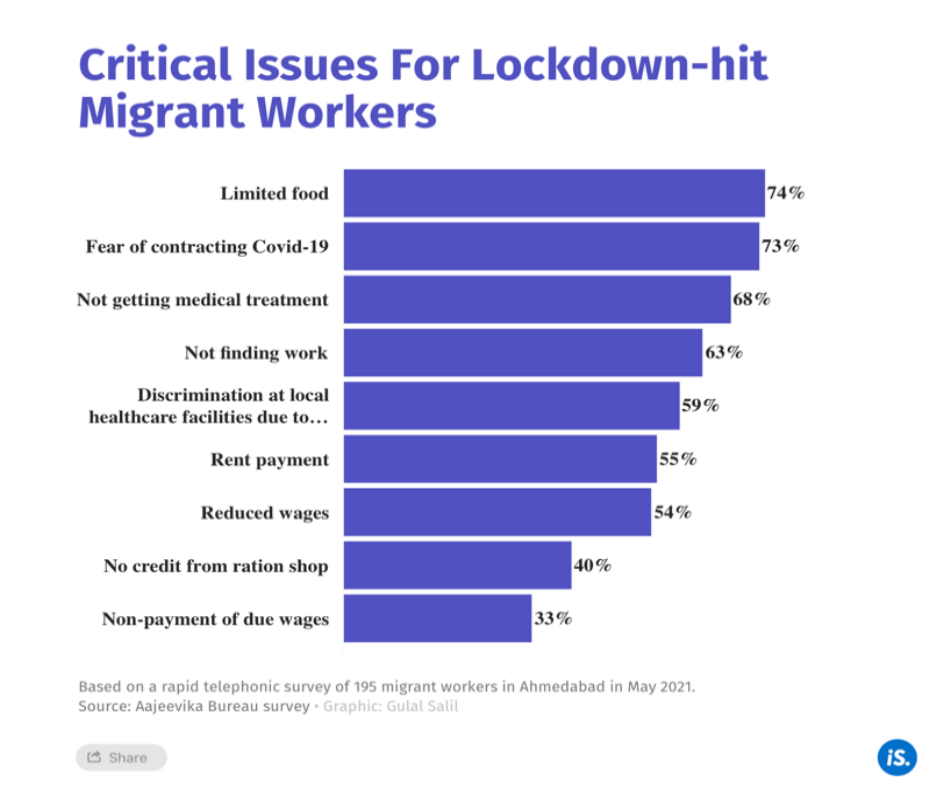

Globally, trade was effectively shut down, and affected stakeholders desperately attempted to cut down their losses. Cost-cutting measures soon trickled down to the most economically vulnerable and triggered a mass exodus in the ranks of the migrant working population. Migrant workers, who sought better opportunities in prosperous regions, now faced a dilemma. Stranded by lockdown restrictions, they were unable to return home and faced severe financial constraints to sustain themselves in their current state of unemployment.5

India descended into a state of utter chaos and confusion. Many migrant laborers were seen walking hundreds of kilometers along highways, desperately trying to make it back to their villages; some did, while others sadly succumbed to exhaustion.6 The Kafkaesque bureaucracy made it difficult for the affected to access relief packages provided by the Government.. When the first wave of the pandemic hit, millions of people lost their lives. Hospitals were not equipped with enough beds, and people died waiting for treatment at the hospitals.7

The Indian Government faced deserved scrutiny for its inadequate response from both the Indian and international media.

The world’s largest democracy was faced with an acute shortage of essential health commodities. Price gouging became an additional bane for India, as reports emerged of oxygen cylinders being sold at a 725% markup and oxygen concentrators at a 500% markup8. Medical professionals struggled with inadequate access to personal protective equipment (PPE).9 Soon sanitizers became a symbol of opulence for India. Numerous establishments shut their doors and employment opportunities dwindled. Amidst this dire landscape, millions of low-wage laborers grappled with the uncertainty of securing their next sustenance.

The Pandemic and the Severity of its Impact on SHGs

SHGs in India found themselves in the eye of the storm. The lockdown and well-meaning, but stringent restrictions imposed by the Government of India to contain the spread of the virus brought their income-generating activities to an abrupt halt. Members were left unemployed and, with meagre finances, their families were pushed further into the clutches of poverty. During the pandemic, bustling markets and bazaars, where self-help groups (SHGs) had thrived for years, transformed into desolate landscapes. Access to credit, which was vital for Indian SHGs to establish and grow their small businesses, became scarce as the economy tightened its belt due to COVID-19. SHGs fostered not only economic empowerment but were also vehicles for social cohesion and support. The pandemic tore at the very fabric of close-knit communities, leaving large swathes of the population in a vulnerable state of emotional turmoil, isolation and abandonment. The loss of livelihood, empty markets, limited access to credit, and strained social cohesion left self-help groups grappling with immense challenges.

The Recovery made by SHGs and how they propelled the economic recovery of India

I have classified the key aspects of how SHGs in India successfully bounced back from the unique challenges posed by the pandemic. Nimble adaptation to the new normal, diversification and innovation, crucial support from the Indian Government, and social and community engagement played pivotal roles in their resilience and success during the challenging period.

- Adaptation to the New Normal: During the pandemic, SHGs faced significant disruptions in their regular activities due to lockdown measures and social distancing guidelines. To overcome these challenges, they swiftly adapted to the “new normal” by embracing digital solutions. SHGs leveraged virtual meetings, communication tools, and online platforms to stay connected, share knowledge, and support members. A remarkable digital transformation not only bridged physical distances but also strengthened the sense of

community within SHGs. - Diversification and Innovation: In response to changing market dynamics, SHGs displayed remarkable agility by diversifying their activities and exploring new avenues for income generation. They utilized their existing skills and resources to produce essential items such as masks and sanitizers, contributing to the fight against the pandemic, while generating sustainable income. Additionally, some SHGs ventured into emerging sectors, such as online retail or agriculture-based enterprises, tapping into new opportunities presented by the post-pandemic landscape.

- Support from the Government: In support of SHGs and their transformative potential, the Indian Government implemented measures to aid their recovery. This included special loan schemes, interest subsidies, and streamlined processes to ensure ongoing financial inclusion and access to credit. These measures not only facilitated the recovery of SHGs but also played a vital role in stimulating economic growth at the grassroots level, empowering individuals and communities to rebuild.

- Social and Community Engagement: Over and above showcasing remarkable economic resilience, SHGs demonstrated a strong sense of social responsibility and community engagement. SHGs actively participated in disseminating critical health and safety information, conducting awareness campaigns, and organizing relief efforts for India’s most vulnerable. Through their collective actions, SHGs emerged as beacons of hope, driving positive change within their groups and making a significant impact on the larger

communities they served.

How SHGs contributed to India’s socio-economic bounce-back from the pandemic

SHGs, mostly led by women, supported the Government by providing essential commodities to battle the pandemic. As per a Forbes India article, as of August 3, 2020, women-led SHGs had produced around 170 million masks, 5.3 million pieces of protective equipment, 5.1 million liters of sanitizer, and operated 1.228 million community kitchens.10

During the COVID-19 pandemic, self-help groups (SHGs) played a remarkable role in various parts of India. In Tamil Nadu, two SHG volunteers monitored queues at Public Distribution System (PDS) shops to ensure social distancing. In Odisha, rural women affiliated with SHGs produced over 1 million cotton masks for the protection of police and healthcare workers.11

SHGs also aided the central and respective state governments in tackling the challenges faced by displaced migrant laborers referred to earlier. Many migrant laborers lost their livelihood during the pandemic. Though some made it back to their hometowns, they continued to struggle to sustain their households in the absence of a regular income. And then there were those who were still stranded at their places of work.

A large number of SHGs became key centers for information for the migrant population. Self-help groups, on multiple instances, helped migrant laborers return to their villages, arranging food for them, as also for others who were vulnerable, desperate and hungry. A few SHGs in Jharkhand and Bihar opened a 24×7 helpline to provide verified information to migrant laborers on evacuation and return processes to their hometowns. In the post pandemic recovery phase, many of these helplines turned into what the ‘International Institute for Environment and Development’ has termed “Embassies for Migrants” and continue to deal with enquiries involving non-compensation, tragedies, accidental deaths.12

The Government of India released funds for feeding people in need during the pandemic. However, migrant laborers unfortunately often found themselves excluded from almost all forms of public food distribution schemes, as they carried so-called ration cards issued by their respective home states, not by the state they were stranded in.13 SHG-led community kitchens became God-sent for millions of India’s informal workers left jobless and stranded.

The collective efforts of SHGs in India played a pivotal role during the pandemic, contributing to the nation’s socio-economic recovery. They produced essential items, supported the government’s response, and showcased resilience and adaptability in manufacturing masks, operating community kitchens, and more. They were also instrumental in assisting displaced migrant laborers, serving as centers for information, arranging for transportation, and providing food. During the pandemic, SHGs created a remarkable safety net for the vulnerable and marginalized sections of Indian society and provided a lasting impact on India’s eventual recovery and transformation.

Resilience, Empowerment, and Growth: Indian SHGs and the Convergence of Drucker’s Principles

The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented challenges to societies worldwide, and India was no exception. However, amidst the chaos and uncertainty, Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in India emerged as beacons of hope, demonstrating resilience, empowerment, and growth. Their efforts align with the management principles of the legendary Peter F. Drucker from about half a century ago.

I. Resilience and Management by Objectives:

In the face of adversity, SHGs showcased remarkable resilience by swiftly adapting to the new normal. Much like Drucker’s principle of Management by Objectives (MBO)14, SHGs set clear objectives for themselves, focusing on the well-being of their members and the communities they served. They identified challenges, such as disrupted livelihoods and food security, and developed strategies to address them. By aligning their objectives with the larger goal of community welfare, SHGs navigated effectively through the crisis, offering

support and stability to their members.

II. Customer-Centric Approach and Empowering Communities:

Drucker emphasized the importance of a customer-centric approach, and although SHGs do not have customers in the traditional sense, their approach is community-centric (as their customer is the community which they build and serve). By empowering communities through education, skill-building, and self-development, SHGs enabled individuals, particularly women, to challenge traditional gender norms and contribute meaningfully to society. This aligns with Drucker’s belief that organizations should create and satisfy customers, in this case, empowering individuals and, in the process, communities to become agents of change and social progress.

III. Decentralization, Knowledge Work, and Grassroots Innovation:

Decentralization15 and the recognition of knowledge workers16 as a vital resource are two pillars of Drucker’s management philosophy. Indian SHGs exemplify these principles by operating at the grassroots level, empowering members to make decisions and take ownership of their and the community’s economic and social well-being. By embracing the unique capabilities of their members, SHGs foster grassroots innovation, with individuals developing innovative solutions to local challenges. This bottom-up approach, akin to Drucker’s call for decentralization, spurred economic recovery and social transformation during and after the pandemic.

IV. Continuous Improvement and Innovation:

Drucker emphasized the importance of continuous improvement and innovation for entrepreneurship to remain competitive17, and SHGs embraced this mindset during the recovery phase post pandemic. By reflecting on their experiences, conducting audits, and re-adapting their practices, SHGs fostered a culture of learning and growth. They encouraged members to explore new opportunities, diversify income streams, and enhance their skills. This commitment to continuous improvement and frugal innovation provided the country with a plethora of microentrepreneurs who spurred the economic recovery of the nation and contributed to its overall resurgence.

“Innovation is the specific instrument of entrepreneurship. The act that endows resources

with a new capacity to create wealth.”

-Peter F. Drucker

Conclusion:

The journey of SHGs in India during and after the COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies the remarkable convergence of Peter Drucker’s management principles with real-world resilience, empowerment, and growth. This alignment between the success story of Indian SHGs and Drucker’s principles highlights the universal applicability of management philosophies in diverse contexts. The collective effort by SHGs, driven by their commitment to community welfare, embodies the essence of Drucker’s vision for organizations and society at large. As India navigates its economic recovery with cautious confidence, the vital lessons learned from the experiences of its SHGs during the pandemic and the enduring wisdom of Peter Drucker’s management principles continue to shape a future for the nation that is more resilient, empowered, and inclusive.

About the author:

Abhishek Banerjee (IN) Abhishek, an undergraduate Economics student at the University of Calcutta, is a fervent supporter of Chelsea FC and an F1 enthusiast. During his leisure time, he works as a freelance sports writer, primarily focusing on these two sports. Abhishek‘s intellectual curiosity has led him into developmental economics and global affairs. Abhishek aspires to channel his energies and talents towards making a positive impact on the world around him.

References:

1: Farrer, Martin. “India is quietly laying claim to economic superpower status.” The Guardian, September 12, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/sep/12/india-is-quietly-laying-claim-to-economic-superpower-status

2: Senapti , Ashis. “Pisciculture gives new lease of life to women in Odisha’s Kendrapara villages”, The New

Indian Express, Jan 17, 2020. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/odisha/2020/jan/17/pisciculturegives-new-lease-of-life-to-women-in-odishas-kendrapara-villages-2090700.html

3: Post News Network, “Fish Farming lets SHGs script their success story”, OrissaPost, Jan 14, 2022.

https://www.orissapost.com/fish-farming-lets-shgs-script-their-success-story/

4: PIB Delhi,” Schemes for Women through Self Help Groups”, Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD) ,March

29,2022. https://rural.nic.in/en/press-release/schemes-women-through-self-help-groups

5: https://infogram.com/critical-issues-for-lockdown-hit-migrant-workers-1hdw2jp0prrpp2l

The Ajeevika Bureau is a public service, non-profit organization seeking to provide solutions, services and

security to millions of India’s rural migrant workers. https://www.aajeevika.org/about_us.php

6: Scroll, “Covid-19: At least 22 migrants die while trying to get home during lockdown”, Scroll.in , March 29,

2020. https://scroll.in/latest/957570/covid-19-lockdown-man-collapses-dies-halfway-while-walkinghome-300-km-away-from-delhi

7: Crawford, Alex. “COVID-19: People dying on pavement as coronavirus crisis stretches India’s healthcare

system to limit”, Sky News, April 24, 2021. https://news.sky.com/story/covid-19-people-dying-on-pavementas-coronavirus-crisis-stretches-indias-healthcare-system-to-limit-12285080

8: https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/976/cpsprodpb/1BB1/production/_118198070_black_market-nc.png.webp

(data from – Pandey, Vikas. “Covid-19 in India: Patients struggle at home as hospitals choke”, BBC , April 26, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56882167)

9: Mishra, Dheeraj. “Doctors Are Running Out of Protective Gear. Why Didn’t the Govt Stop Exports in Time?”,

The Wire, March 25, 2020. https://thewire.in/government/coronavirus-protective-gear-doctors-ppe-indiaexports

10: Shekhar, Divya. “The economic potential of women self-help groups”, Forbes India, August 3, 2020.

https://www.forbesindia.com/article/special/the-economic-potential-of-women-selfhelp-groups/61329/1

11: Bhowmick , Soumya.“COVID19 and women’s self-help groups”, Jul 21, 2020, Fortune India.

https://www.fortuneindia.com/opinion/covid-19-and-womens-self-help-groups/104667

12: Bharadwaj, Ritu.“A helpline that is a lifeline for migrants”, Jun 1, 2022, IIED. https://www.iied.org/helplinelifeline-for-migrants

13: PIB Delhi,” Community Kitchens run by SHG Women provide food to the most poor and vulnerable in Rural Areas during the COVID-19 lockdown”, Ministry of Rural Development (MoRD) ,April 13,2020.

https://rural.nic.in/en/press-release/schemes-women-through-self-help-groups

14: Drucker, Peter. The Practice of Management, New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1954.

15: Drucker, Peter. The Concept of Corporation, New York, NY: John Day, 1946.

16: Drucker, Peter. The Landmarks of Tomorrow, New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1959.

17: Drucker, Peter. Innovation and entrepreneurship: Practice and principles, Boston, MA: Butterworth

Heinemann, 1985.