In innovation and transformation we have avoided looking at the structural transformation of industries. This is arguably due to the fact that so many industries are changing at the same time, making the analysis of structural change an overwhelming task. Other reasons include: the fact that the change driver is not technology and nor is it an exogenous shock such as a fast rising emerging economy. Instead we have moved into an era where a combination of factors can quickly fragment an industry from tight vertical integration to broad horizontal dispersion.

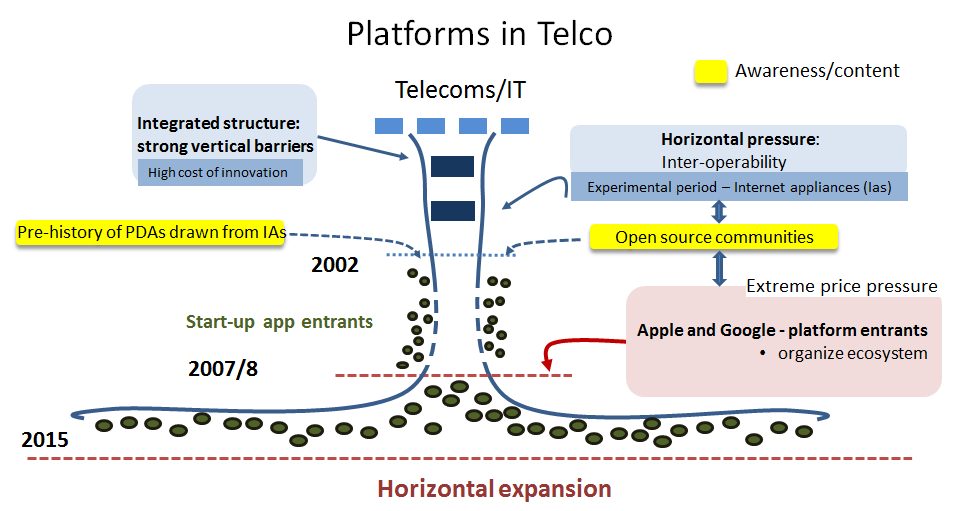

The diagram below summarizes disruption forces in the IT and telecoms space from the late 1990s onwards. Reading the diagram from the left, it says that telecoms was a highly consolidated sector comprising network carriers, network infrastructure and device makers.

Telecoms used to be dominated by cartel-like relationships between large carriers, large phone makers, infrastructure providers, and their carrier software support vendors such as the ERP giants. It was almost impossible for a small company to do business with in this environment.

In IT, the entrepreneurial community had attempted to by-pass Microsoft’s control of operating systems (OS) by gravitating to a new device, an Internet appliance that would need its own OS. This was tried by the highly experimental BeOS. BE came close to success but not close enough. The cartel held sway.

Be was started by ex-Apple employees. The migration of key staff is a significant source ofcreative destruction.

Be employees, in turn, went onto Android, which started its life as an attempt to build an OS for Internet appliances

The intra-community activity between these companies created a significant store of experience as well as belief that business could be done differently.

At the same time that Internet entrepreneurs tried to gain traction, a burgeoning Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) market was emerging. This market had been growing and by the mid-2000s, was Internet enabled. It was the precursor of the smartphone in design and personnel.

An apps developer ecosystem was also well established within PDAs. Palm had 50,000 applications before Apple thought about an App Store. There was a well-worked out methodology to assess effectiveness of these innovations, based on consumer feedback and web analytics.

This was the situation when Apple launched the iPhone in 2007 and when Google launched the first Android phones a year later.

One catalyst for change – applications written for mobile devices – was only manageable at the scale reached by companies that had a strong platform background, as both Google and Apple had. Their arrival presaged a period of six years where the rule of management has not been to stick to the core – it has been to seek out the adjacencies.

Apps created a huge well of free content or usage opportunities for smartphones.

And on pricing, high end smartphones could cost $600 – 1000; on the cheap end though they quickly became available for $150 – $250. Radical price reduction is a feature of dramatic change.

There was also structural innovation – the upgrading of the US telecoms networks and with it the new information layer around sites like TechCrunch, who belatedly realized mobile) was an industry to rival and exceed computing. They became strong advocates of Silicon Valley products. Finally the mobile grid became truly global, laying an infrastructure for new ways to do business at scale with low unit costs.

That brief overview of events fits the model above as discussed in the first post. Here’s how it fits banking.

- Concentration and the development of hubristic conditions. Bank consolidation preceded the Great Recession and was an integral part of the solution. Since the crisis we have seen considerable evidence of hubris (such as LIBOR fixing).

- Experimental era. The finance sector has been surrounded by innovators seeking ways to pull down the walls of the oligopoly since the early 2000s (PayPal, Internet banking, low cost security brokerage; In retrospect it is surprising that so little of these gained traction, in the sense of creating a vibrant innovation culture.

- The Content Layer. The growth of awareness and experience among consumers of different forms of substitute products and services has grown over a 10 – 15 year period but more than anything the crisis has created a new information environment.

- Ecosystem consolidation. Over the past three years Fintech funding has grown three times faster than all VC funding; BitCoin and Ripple have now introduced the disruptive threat of open source and banks themselves are seeking a role in open source project.

- Platform: Banks are all actively pursuing adjacencies, partnerships and fintech investments. Will another venturer provide the platform to consolidate this activity and renew finance? Already the space is becoming crowded with tech giants and new vendors in specialized areas like trade and supply chain finance, each taking the concept of finance beyond a traditional bank boundaries.

People are migrating between each and all of traditional banking, new finance companies tech platforms experimental era entities (PayPal), and start-ups. The people flow presents real opportunities for companies, incumbent and new, to create new market structures and it reflects a widespread belief that the structure can be and will be changed.

On the technological front, the advent of global mobile networks makes it possible to conceive of ultra-low cost payments’ networks The essence of change though lies in using scale on global mobile networks to make payments a true Internet service with the capacity for individuals and companies to deal with each other without intermediaries, therefore putting pressure on intermediaries to create new types of value rather than just to extract rent. Apple (phone payment via credit card), Google (email payments), Twitter and Facebook (social payments) are not taken seriously enough as future payment infrastructures, yet they operate at a scale most banks don’t yet dream of.

These companies have the capacity to make payments virtually free to the end user, akin to the impact of apps on the mobile business. Other tech companies have the capacity to make working capital and other types of loans to business at rates that don’t need to reflect high fixed costs. By opening up credit lines for businesses tech companies can position themselves to be the provider of all kinds of planning, execution and supply chain coordination software. In transaction banking the process of externalizing functions is creating a new market for payments providers of all types. Here payments are coupled to the changing needs of the enterprise, so the actual payment is subsidiary to services like credit lines and complex fx hedging. There is no need for an enterprise to rely on banks for these services and as non-bank credit lines are opening up and banks will find ways to fund trade without having loans on their own balance sheets.

These examples suggest there is a pattern in structural disruption. Entrepreneurs destroy industry structures, often for ideological reasons; and oligopoly is its own enemy because it leads to poor decision-making. Executives who want to anticipate disruption need to look closely at these factors. Disruption is, after all, predictable.

A longer version of these posts can be found here.

—

A blog following the Global Peter Drucker Forum 2014. An opportunity to share experiences and learn from one another in the context of The Great Transformation.